CFO agility — challenged in recent years by the COVID-19 pandemic, Silicon Valley Bank’s failure and war in Ukraine and the Middle East — is facing a new test as turmoil in the U.S. Presidential election has quickly ratcheted up domestic geopolitical risk and uncertainty, corporate finance experts say.

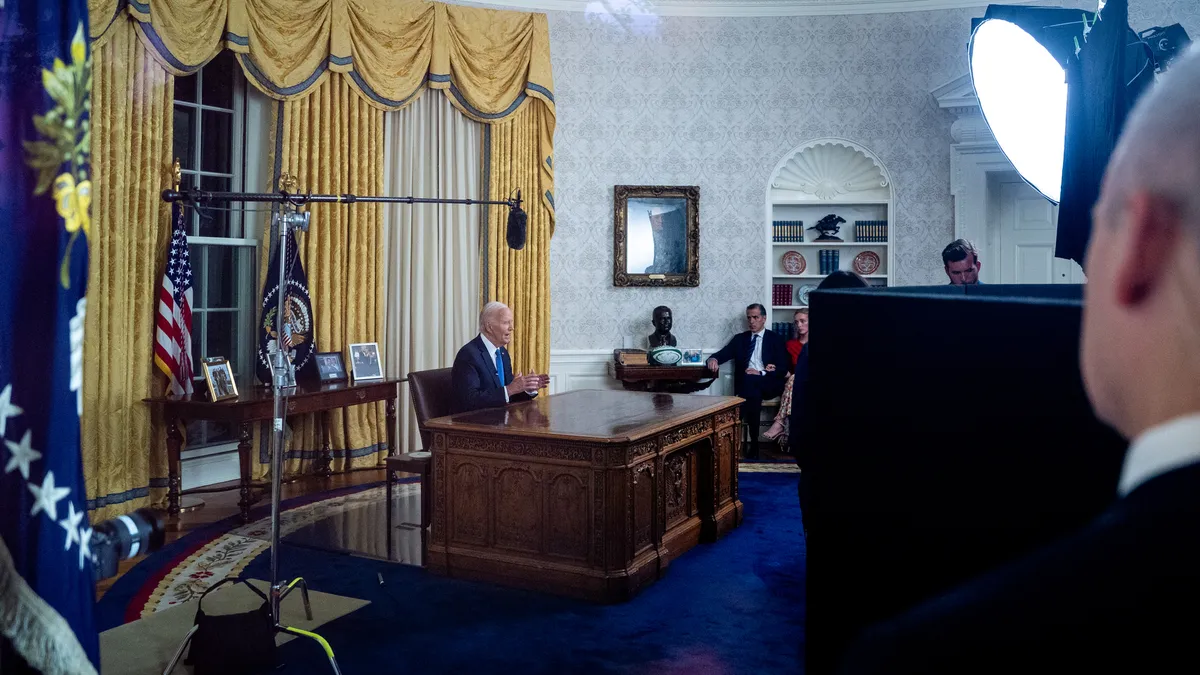

In a one-two punch of extraordinarily unusual political events that played out over the course of about nine days, the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump on July 13 was followed by President Joe Biden's subsequent announcement on July 21 that he was not seeking reelection and had decided instead to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris. In the midst of it all, a CrowdStrike software glitch unleashed massive technical disruptions across industries on July 19 in what’s been called the largest IT outage in history that will hit Fortune 500 companies with more than $5 billion in direct losses, according to CNN.

“It’s really tough when you put together these three massive events in a two-week period and try to find the right combination of crystal balls to figure it out,” Bobby Mikkelsen, CEO and CFO of the Las Vegas, Nevada-based Tego Cyber, said in an interview. “You put all those three things together and if anybody says they have all the answers today they’re full of [it] because all the different scenarios that could be developing out of those three things are large.”

Like many executives and voters, Mikkelsen said he was still evaluating the potential fallout that the events could have on his cybersecurity software company. But already he’s concerned about the impact on the climate for financing which is the lifeblood of early stage companies like his. He’s not expecting capital to be “coming out in droves over the next three and a half months — and even less so because of the last two weeks,” he said.

New threats in a ‘polycrisis’ era

The election shakeup is only the latest disruption in what some call a “polycrisis” era. The term, coined by Adam Tooze, a Columbia University history professor, denotes a world buffeted by crises that can spill into one another, like climate change that can dislocate people and lead to immigration, the Financial Times reported.

To be sure, finance experts and executives hold a range of views on the relative import that the presidential election’s turmoil will have on business as compared to other crises CFOs have grappled with in recent years. But many say that the political shakeup, at least for CFOs, pales in comparison to the pandemic and the regional banking crises which slammed the corporate finance world squarely at its core.

“When you think about SVB, that led treasurers to really have to think, ‘is my liquidity really what I think it is, do I have to rethink my banking partner?’ It was a direct impact on the financial system,” Stephen Philipson, head of wealth, corporate, commercial and institutional banking at Minneapolis, Minnesota-based U.S. Bank said in an interview. During the pandemic, there was a fear of what “tomorrow was going to look like” along with “zero visibility” on cash flow, he said.

In comparison, the tenuousness of the election’s outcome does not have a direct and immediate impact on businesses, even as the unprecedented nature of the turmoil around the events is very “front of mind” for CFOs and treasurers, he said. “There’s visible uncertainty,” Philipson said. “There is predictability in that we have two potential paths and I think people have a general idea of what each party would do if [they were] in office.”

Blind corners

Even before the singular political events of late scrambled the presidential race, executives — as they typically do ahead of all major elections — were bracing for the election and the potential policy changes that different outcomes can bring.

In early June, nearly one-third of CFOs signaled that their companies were postponing, scaling down, delaying or permanently canceling investments due to uncertainty around the upcoming election, according to a survey that closed June 3 that was a joint initiative of Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and the Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond and Atlanta.

In contrast, after Biden announced he was getting out of the race, the CFO Leadership Council sought to gauge finance chief sentiment in a one-question LinkedIn survey that asked whether CFOs felt the upcoming U.S. elections would impact their strategic planning. A majority (78%) of the more than 800 finance chiefs surveyed felt the upcoming U.S. elections would affect their plans in some way, with 20% anticipating a significant impact, 31% a moderate one and 27% a minimum impact. Only 22% said it would have no impact at all.

The bottom line is that CFOs are divided on their views of the impact of the election outcome, in part because the varied nature of businesses mean policies affect them very differently or not at all, Jack McCullough, founder and president of the CFO Leadership Council said in an interview. For example, a company that competes with goods made outside the U.S. would welcome the 10% tariff on all imports proposed by Trump while one that buys imported goods could see their margins squeezed, he said.

But what the survey didn’t tackle was the angst that the new uncertainty piles onto CFOs who crave strong data they can use to support the solid forecasts and strategies that they need to deliver to their boards and companies. “For CFOs, the thing they like best in their professional lives is certainty…and when you’re living in a volatile environment as we have been for four years it’s probably the worst-case scenario,” he said, noting that a previous tongue-in-cheek survey found that the most popular super power craved by finance leaders was “seeing around corners.”

Accelerated issuance, hedging

CFOs have been dipping their toes into the market to offset some of the risks they are seeing. In a U.S. Bank survey back in January and February of more than 2,000 executives, the share of respondents who named geopolitical risks as a top worry rose to 26% from 17% in the year earlier, CFO Dive previously reported, with an increasing number of CFOs and treasurers hedging against interest rate risk and shifts in foreign exchange and commodity prices.

“Even though the market seems to react in a less volatile fashion to these big news headlines that would have been major market movers in the past, I think finance executives are still very cognizant of identifiable risk, whether it’s the presidential election or the wars going on around the world,” Philipson said in an interview last week. “And the last two weeks demonstrate that there’s also unidentifiable risk that can pop up.”

As a result, he said one of the things the bank has seen a lot more this year is an increased use of FX option strategies that companies are using as a way to cap their downside risk. For example, they’re buying call options, effectively locking in the ability to buy or sell a currency at an out of the money price as a potential against downside risk. That’s no longer just for the biggest corporations; even middle market companies are increasingly using such hedges to offset the possible impact of an election or central bank policy move that can affect the dollar’s strength relative to other currencies, he said.

At the same time, many companies have already accelerated corporate debt issuance this year, a pull-forward of activity that Philipson attributes in part to companies seeking to avoid any potential election volatility. The volume of U.S. investment-grade corporate bond issuance passed the $1 trillion mark on Wednesday, well ahead of the September date it crossed that threshold in 2023, Philipson said. That's the second earliest date historically that investment-grade corporate debt issuance has reached that level, according to U.S. Bank data. Only in 2020 did the issuance surge any earlier, an outlier year that saw the $1 trillion milestone passed in May as companies across industries scrambled to shore up their balance sheets.

While financing volumes are always slower in the second half, Philipson said that as long as risk markets remain stable there could still be a steady amount of supply in the second half of the year, especially given that there’s a big wall of early pandemic debt that will need to be refinanced next year.

Of course, there are political changes afoot outside the U.S. that could have a range of implications for various corners of the global economy. For example, the U.K. election earlier this month led to Labour Leader Keir Starmer becoming prime minister, but it’s not clear what that’s going to mean for M&A, David Dean, managing director of M&A at Willis Towers Watson, said in an interview.

Do get educated, don’t overreact

While Biden stepping down is a clear signal of coming change, the important thing for CFOs to do right now is “get educated, but be patient,” Connor Augustyn, director of financial operations and private equity at West Monroe told CFO Dive.

It’s important for CFOs to pay attention to any key differences that may emerge between the Biden and Harris platforms. Ultimately, this juncture should serve as a catalyst for finance chiefs to ensure their organizations are well-prepared to weather change, Augustyn said in an interview.

“I would say since COVID, this has become the second-largest business disruption that's forced CFOs to pause and say, ‘How do I plan for agility?’” he said. “So it's become a good catalyst for them to look introspectively and say, when the change comes, ‘How do I quickly pivot my organization to make sure that we are not behind the eight ball?’”

Finance chiefs also should be sure not to overreact — for West Monroe’s part, the consultancy has been coaching finance chiefs through a “standard election” where both parties have different views on corporate policies, taxes and regulatory, he said, despite the tumult of recent events.

What CFOs can do in practice to prep for any coming changes is examine their core business processes to make sure they have the flexibility they need — if new tariffs are placed on imports, for example, and subsequently impact product costs, “how quickly can my organization put a product cost change and a pricing change out to the market?’” Augustyn said.

The FP&A team will play a critical role — ensuring that needed flexibility “comes through making sure that your FP&A organization is very sound…but then it's also taking a look across the organization and understanding where you may be slower to move because of inefficiencies in processes, technologies,” he said.

With so much coming at businesses today, the real challenge for finance chiefs is making sure you’re being proactive and not reactive, said Myles Corson, global and Americas strategy and markets leader, financial accounting advisory services for Big Four firm Ernst & Young said.

“I think for CFOs, the big challenge is, if you don't have a clear vision of where you're going as an organization, and where you're going as a function…you can get overwhelmed by reacting to all of that disruption,” he said, adding that the outlook for interest rates and what that means for capital investments probably remains a bigger concern for CFOs. It’s critical, he said, for CFOs to be able to “see through some of the short-term noise of the news cycle.”

Editor’s note: Alexei Alexis contributed to this report.