It’s looking like this time could be the charm for a move to update U.S. accounting standards to require more explicit breakdowns on the income taxes corporations pay — and where they pay them.

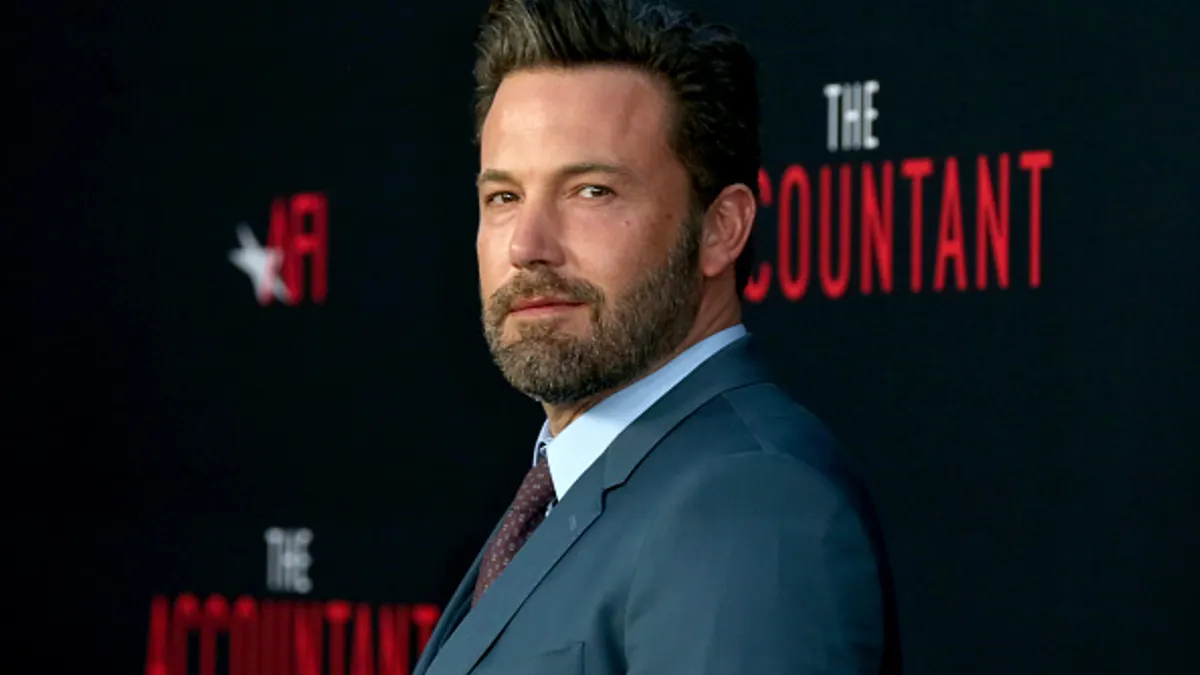

The matter was tabled the two prior times the Financial Accounting Standards Board considered requiring the disaggregated tax information disclosed, KPMG Partner Brett Weaver said in an interview. Now — with the FASB’s proposal to update its income-tax standards out for public comment through May 30 and the pendulum of public sentiment swinging to support more corporate transparency — Weaver doesn’t believe it’s going to end that way again.

“Its time has come,” Weaver said of the new tax rules, noting that the FASB exposure draft dovetails with a broader global push for tax transparency as an element of environmental, social and governance initiatives and mandates. A number of jurisdictions around the world are moving to raise the bar on tax disclosures and getting away from the days when companies could choose what they disclosed, with many providing the “bare minimum” of tax information, he said.

The proposal has drawn pushback from businesses in the past. But Weaver, the tax leader for the ESG practice at KPMG U.S., pointed to a number of recent signs that the FASB’s plans may have extra tailwinds this time. Those include growing shareholder interest being tested through proxy votes and a signal of support from the Securities and Exchange Commission. In September, SEC Chair Gary Gensler told the Senate Banking Committee that he thought the disaggregation the FASB was considering would be a “productive approach,” according to a September 15 Bloomberg Law report.

If the proposed changes goes forward the more stringent standards call for companies to disclose income taxes paid on a disaggregated basis to federal, state and foreign entities and companies would also be required to identify any jurisdiction — such as a country or state — that receives over 5% of its total tax payments, as CFO Dive previously reported. Under current standards, companies aren’t required to provide such breakdowns.

“That’s really going to change the game in terms of what’s disclosed about a company’s tax affairs,” Weaver said. It also poses the potential for new rewards and risks for finance leaders thinking about their tax strategy.

Shaping the narrative

For example, on the plus side, increased tax transparency can be an ESG-friendly piece of corporate strategy even though its role may not be as obvious as those played by greenhouse gas emissions reduction or other climate-related projects. Weaver said corporate tax ties into multiple elements of ESG programs.

“The transparency piece is in the S and the G because the view here of a responsible taxpayer is paying a fair share of tax and that corporate taxes are necessary for funding social programs, schools and all the rest,” Weaver said.

However, the disclosures will likely raise questions if they show that a company’s tax rates are meaningfully above or below the statutory rate, Weaver said. That means executives will need to take control of the narrative and explain why it is so. In either case anomalies will need to be addressed, he said.

“If it’s above, there’s probably going to be questions about why the company’s not able to manage its tax affairs in a way that it’s paying an expected amount of tax — ‘Why is it so high?’,” he said. On the flip side, Weaver said if the rate is meaningfully below expectations the company will need to explain the tax strategy that’s yielding that result and why the company is still paying its fair share.

For example, he said, if a company has an effective corporate income tax rate of 17% even though it would be expected to be 21%, they might want to explain that they pay a substantial amount of import duties and indirect taxes because of the nature of their business, which effectively raises the taxes they pay but are not reflected in the income tax rate.

Weaver expects new FASB tax standards may ultimately be effective in 2025. And, given the global shift in tax sentiment, companies will need to begin preparing to explain their tax positions — both inside and outside the U.S.

“The old days of disclosing what we had disclosed in the past are gone. It’s going to be much more transparent and much more granular,” and that will require companies to think about how they will frame their tax stories, potentially even providing additional information above and beyond requirements to explain their strategies, Weaver said. “That’s kind of the new world we’re moving into.”