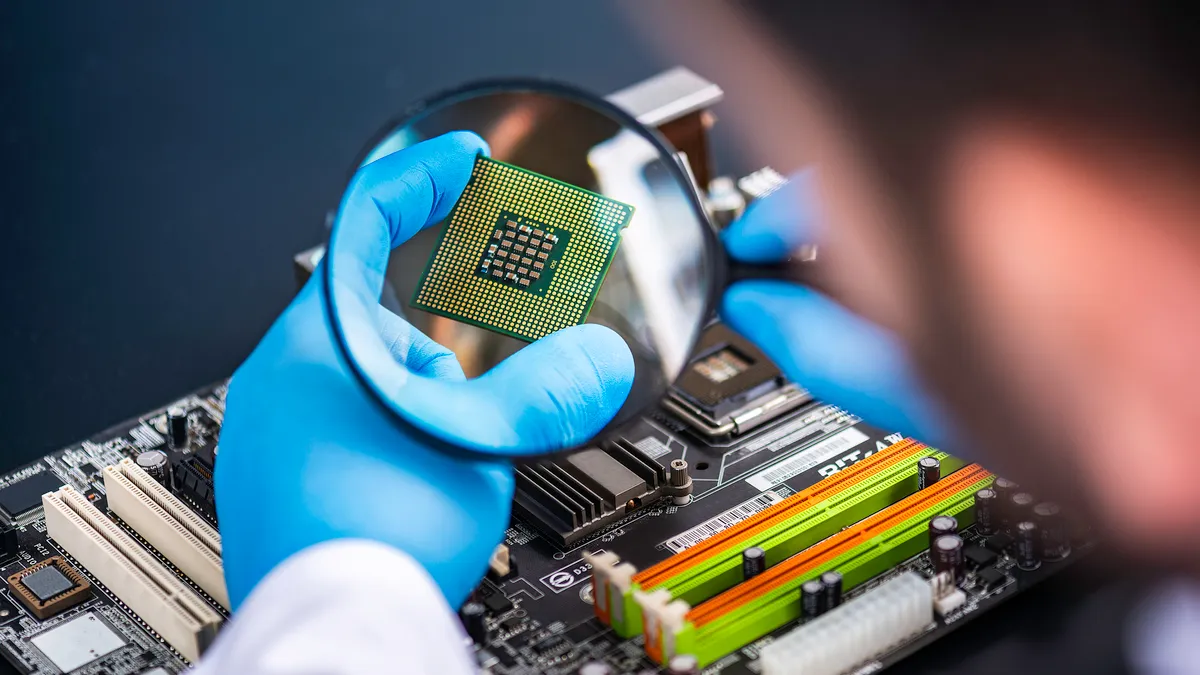

Building resilient supply chains is a strategic priority of the Biden administration, which has launched a sweeping effort to safeguard the supply of semiconductor chips. But the initiative has consequences for pricing and businesses, analysts say.

The CHIPS and Science Act, which was passed last year, allocates nearly $53 billion to support the research and manufacture of semiconductors in the U.S. The legislation is part of a broader effort to bring manufacturing to the American heartland to safeguard national security and economic interests.

It also comes in the wake of a shift by companies worldwide to adapt in the wake of pandemic supply chain by shifting production closer to consumers, CFO Dive previously reported.

Speaking at a Washington, D.C. roundtable conference last week, semiconductor, aerospace, logistics and consumer product industry representatives stressed the importance of balancing the need for building domestic manufacturing capacity while safeguarding market access and trade.

“What the CHIPS Act does is it addresses a couple of major vulnerabilities that we've had; one of them is that we don't manufacture enough chips here in the U.S.,” said John Neuffer, CEO of the Semiconductor Industry Association. “We believe there needs to be a minimum viable capacity here on U.S. shores…we don’t think it should all be done here.”

Reshoring takes time

Neuffer said he was satisfied with the administration’s plans to support domestic semiconductor manufacturing, but he warned that these efforts should not interfere with access to customers located in other markets, especially since 80% of the industry’s customers are overseas, he said.

“China is a very big market for us, and we rely on those revenues to power our research and development,” he said, noting that trade restrictions should be narrowly targeted to address national security concerns and implemented in collaboration with allies.

Eric Fanning, president and CEO of the Aerospace Industries Association, noted that while national security interests are paramount, efforts to bring manufacturing capacity to U.S. shores should be tempered with the need for industry to access international markets.

Bringing production capacity back to the U.S. will also likely take time, he added.

“We have to have a strategy so we can prioritize how we’re doing this,” he said. “Think about rare earth minerals…they're not easy to get out of the ground, and they're really difficult to process, and there just isn't the [domestic] market right now for it.”

Speaking more broadly about reshoring efforts, some noted that industry and government should examine the costs and benefits of reshoring, including when it makes sense to develop manufacturing capacity domestically versus relying on foreign markets.

“One of the things we need to do is step back and figure out where we have a need to make things in the United States and what’s the metric by which you decide,” where investments should go, said Inu Manak, a trade policy analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Costs for consumers

One negative consequence of efforts to reduce reliance on foreign supply chains is increasing costs for the consumer, the communication around which should be well thought out, panelists said.

If a lot of critical technologies are manufactured in the U.S., “I think we're going to raise prices on a lot of American products,” said Manak. “When we're thinking about building up resilient supply chains, and working with our partners towards common goals, we need to do the thinking about our consumer base [around] what we can reliably do here and what we need to import from the rest of the world.”

As a result, trade policy should be closely incorporated into discussions on supply chains, argued David Chavern, CEO of the Consumer Brands Association.

“We have to understand that while supply chains in general have gotten better … They've also always gotten much more expensive, and in ways that don't just reverse themselves,” he said. “We need a continued focus from the government on supply chain and infrastructure, because you can't just do it after the next crisis.”