Many real estate investment trusts have applied lessons learned from the 2008 financial crisis to manage their present balance sheets more prudently and put them in a good position to weather the current economy’s headwinds, Prologis CFO Tim Arndt said.

Among the hallmarks of that playbook: low leverage, pushing debt maturities out when possible and a focus on liquidity, he said. That approach, Arndt said, has left the industrial real estate company Prologis prepared to both seize on opportunities and protect itself amid the current uncertainties stemming from the Trump administration’s April 2 tariff barrage.

“We manage the balance sheet across the cycles both for opportunities and to prepare for these disruptions and in that regard we’re already prepared,” Arndt told CFO Dive in an interview Friday.

What does that financial preparation exactly look like? For starters, while some companies have access to just one credit line that matures every five years, Arndt said Prologis carries three different credit lines, each with roughly 30 banks in them, and overlapping and staggered maturity lines that Prologis seeks to leave largely untapped.

“So tomorrow I could draw down $6 billion and do something with it,” said Arndt. “That’s tremendous flexibility.”

The setup keeps Prologis in the bank markets more frequently, but he said it reduces the risk of needing capital from banks at a single time where there could be a disruption.

The company is also a high-grade issuer of debt, he said, which enables it to borrow at anywhere from 15- to 40-year terms, compared to 10-year terms for lower-rated companies. As of March 31, its credit ratings were A and A2 from Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s, respectively, according to the company’s Q1 2025 filing with the Securities & Exchange Commission.

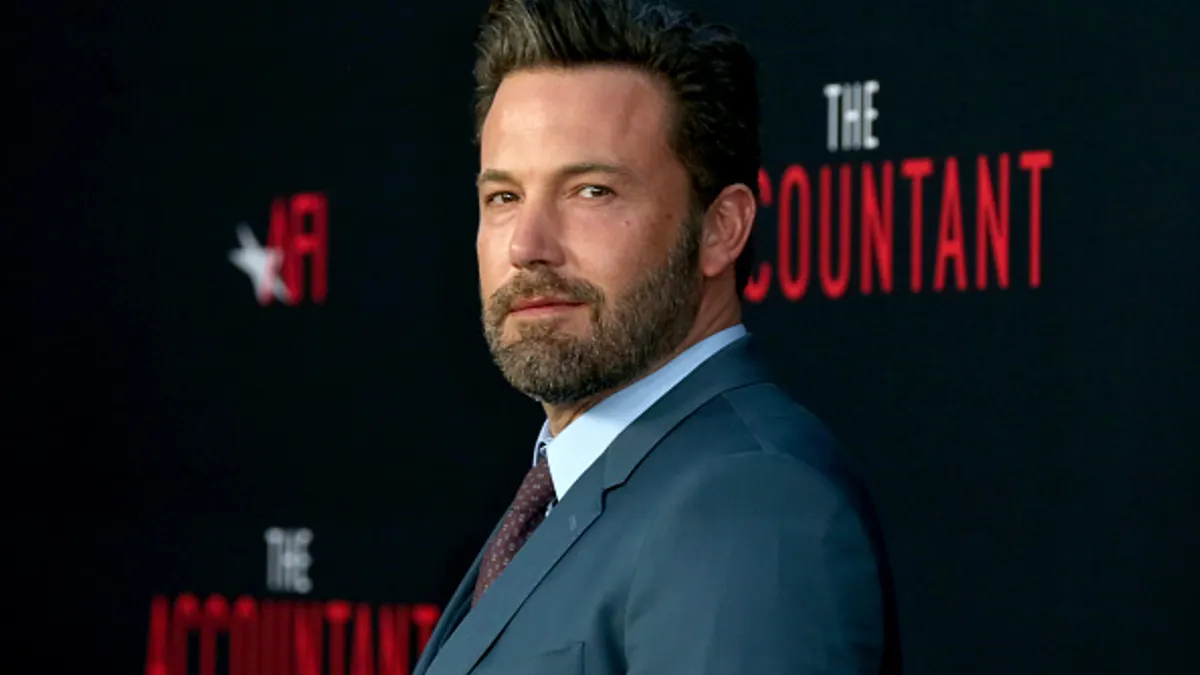

Arndt, who took over as CFO in 2022, spoke about his company’s debt strategy and outlook as the industrial real estate market is said by some to be, along with retail, one of the real estate sectors most exposed to tariffs and their potential affects on the supply chain.

On the company’s Q1 earnings call, Arndt outlined the uncertainty that tenants are faced with while also asserting that a “disconnected world” shifting away from globalization will require more warehouses and potentially increase demand for industrial space.

Asked in the interview to elaborate on his view, he said that his comment was effectively a “directional” one. In an imagined world where there’s no more global trade, each region would need to have space for the entire supply chain: sourcing raw materials, manufacturing goods, storing finished goods, and distributing them.

However, he said Prologis, with a portfolio of warehouses focused on the consumption end of the supply chain, is sticking with that business model and not betting that large amounts of manufacturing will return to the U.S. and create demand for the different elements of the supply chain long-term.

“We don’t believe, from principally the cost and complexity of supply chains that will need to be built in the U.S., that we are going to see significant amounts of production come on shore,” Arndt said, noting that a substantial rise in manufacturing has not occurred since the first Trump administration initiated the higher tariff paradigm.

For now, one gauge the company is keeping a watch on to get a sense of the tariffs’ impact is the utilization rate inside its warehouses, which has not deviated in the U.S. from the roughly 85% typical longer-term norm. It’s still early, he said, “but we’re watching it carefully anyway because it’s a good predictor. You want high utilization in your buildings.”